Rage to riches

We can't beat populism unless we fix wealth inequality. And we can't fix wealth inequality without some windfall taxes on the very wealthiest

I was a card-carrying member of new Labour. I co-founded Progress in the early 90s and rose to office under Tony Blair. But I’m now convinced it is time for some judicious windfall taxes on the very wealthiest. It’s the only way to restore fairness to our tax system and raise the resources we need to defeat the snake-oil of populism.

The Lucky Few

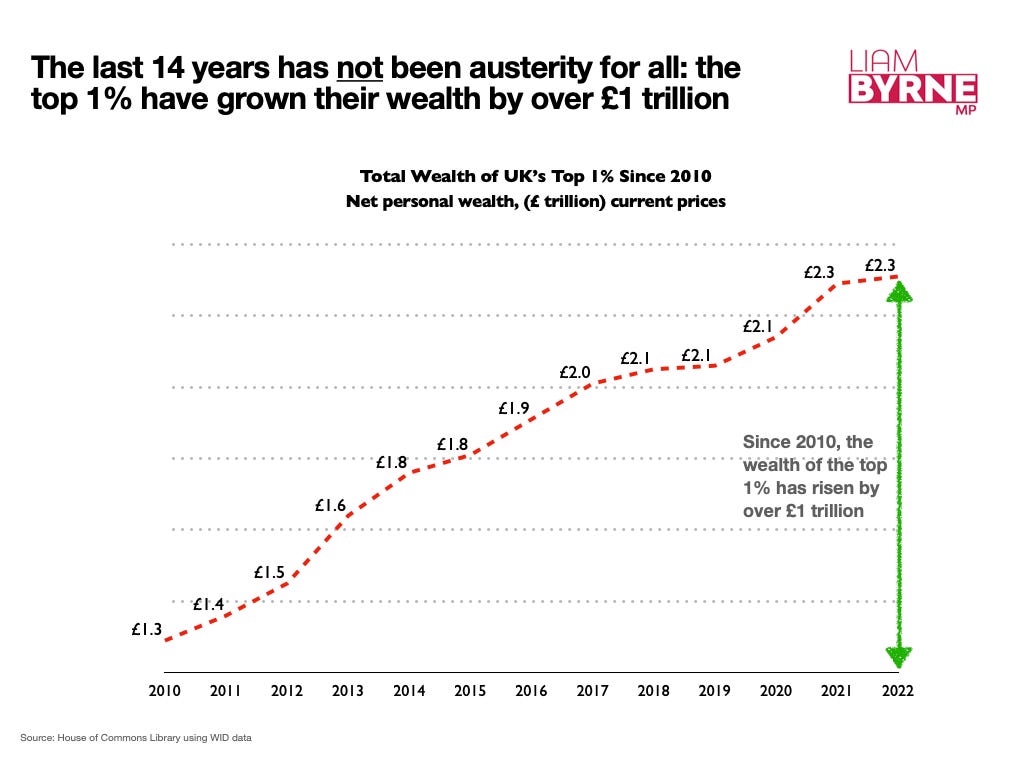

The last fourteen years have been brutal for millions. Austerity has buckled communities like mine in east Birmingham where we now suffer from the worst child poverty in the country. Yet, for a lucky few the last decade and a half have been not the worst of days, but the best of them. Indeed, since 2010 the richest 1% of people in our society have grown their wealth by over £1 trillion.

That means at a personal level, a lucky 1%-er has seen an incredible £2.2 million boom in their fortunes. That is FORTY-ONE TIMES more than the rise in the average wealth of someone in the bottom 99%.

Were the richer just smarter than everyone else? Did they work harder? Win the lottery?

No. In fact, the key to their success has been the incredible £895 billion of quantitative easing (QE) poured into the monetary supply.

This bold move held down interest rates by almost 1% and these low rates account for perhaps three-quarters of the once-in-a-century boom in wealth triggered by soaring assets prices.

Yet, QE is not free. In fact it will cost the taxpayer a fortune. All told, the OBR forecast the great unwinding of the QE programme will end up costing us all £104 billion (OBR. Economic and fiscal outlook – March 2024, chart G).

So, we all paid for QE. But, QE’s prizes went disproportionately to the very richest.

But there’s one thing more. Those lucky enough to draw their income from capital investments enjoy a rate of tax that is much lower than everyone else. Almost 60% of investment income in the UK goes to the richest 10% of households. To people like Rishi Sunak who happens to make about £2 million a year - but only pays a rate of tax of 23%. When one in five citizens are paying over 40% tax, this simply cannot be fair.

The Politics of Wealth Inequality

It will amaze you to hear that this unfairness affects what happens on Election Day. Indeed, a simple analysis of those regions - and those constituencies - where Reform did best lights up a simple truth: those who feel left behind are seduced in greater numbers by the snake oil of populism.

Let’s look at the regional data first.

The data we have on wealth in Britain isn’t great. But when we look at the relative increases in aggregate wealth since 2006/08, and the Reform vote in each region at the 2024 general election, we can see a clear pattern; those regions where wealth grew least - the north east, the East and West Midlands - voted more heavily for Reform. Where wealth growth was biggest - in the South East - the Reform vote was lowest.

This confirms findings in much of the literature on populism and inequality, not least a new study by Andrés Rodríguez-Pose, Javier Terrero-Dávila and Neil Lee out last year which concluded:

“our analysis suggests that grievances over an increasingly uneven distribution of resources, both within regions, in the form of rising local interpersonal inequalities, and especially between leading and left-behind regions, are good predictors of support for far-right populist parties.” (See also Wilkinson, 2019 and Rodrik, 2021) (h/t Rob Ford for the reference)

A different way to look at this is to look at house prices (See David Adler & Ben Ansell’s brilliant work for the theory).

House prices are a reasonable proxy for wealth at a constituency level. When we look at house prices in high Reform-voting seats (which I define as a 30% vote at the general election which is around twice the national average Reform vote once we exclude Scotland and Northern Ireland), we see they’re more than a third lower than the national average. That is almost £120,000. And the gap between house prices in ‘high Reform vote seats’ and average seats is about the same gap as it was 20 years ago. In other words, the places ‘left behind’ twenty years ago have still not caught up by 2023.

Furthermore, the twenty seats where the Reform vote is highest have higher levels of deprivation, a lower proportion of residents with Level 4 qualifications - and a much smaller ethnic minority community.

Let’s take a quick look at the seat by seat correlations. Using data carefully prepared for me by the House of Commons Library, we can see some stark patterns. The constituency average house price almost creates a ‘frontier’ for the Reform vote.

With a few exceptions, once house prices in a constituency rise, so the Reform vote falls back. Seats with higher house prices generally have a lower Reform vote. Indeed, where house prices in a seat hit the national average value, Reform finds it very difficult to break beyond 30% of the local vote.

These patterns becomes clearer where we control for the ethnic diversity of a seat. We know that Reform is less appealing to ethnic minority voters. So when we look at seats with an average proportion of ethnic minority residents, we see just seven constituencies (Old Bexley and Sidcup, Broxbourne, Hemel Hempstead, Buckingham and Bletchley, Sutton Coldfield, Stevenage and Harlow) with above average house prices that deliver above average Reform votes.

The relationship with deprivation is just as stark. Deprivation levels also create a frontier for the Reform vote. And very roughly, a 10% decline in the proportion of residents wrestling with at least one dimension of deprivation, sees a 10% fall in the Reform vote in that seat.

Now, we have to be a bit careful with this analysis.

Prof Rob Ford makes the point to me that many of the groups least likely to vote Reform (viz graduates, migrants, high income professionals) live in places with high house prices while groups most likely to support Reform are overindexed in places with low house prices. So, the economic and social dynamism of a place that attracts internal and international migration might both drive up house prices and attract groups less susceptible to a populist appeal.

I take that point, but I suspect those who have not caught up during the wealth boom enjoyed by the richest, feel left behind. And this has an impact on voting behaviour. I think this because of what we know about the economic beliefs of Reform voters.

YouGov recently found that almost three quarters of Reform UK voters (73%) feel that ‘ordinary working people do not get their fair share of the nation's wealth’ and that:

78% of Reform UK voters feel that rich people in the UK are able to get around the law or get off more easily than poorer people

74% think big businesses take advantage of ordinary people .

69% believe ‘the rich should be taxed more than average earners’

Towards Solutions

These basic truths take me to one inexorable conclusion. To defeat populism, we have to fix wealth inequality. It’s the not the whole of the answer. But it is a big part of the solution.

As it happens this is four-square on the platform Labour stood on. Indeed, when we launched our manifesto, in the words of the Guardian,

“Keir Starmer has vowed to “turn the page for ever” on held-back potential as he put wealth creation and economic growth at the heart of Labour’s manifesto” (my italics).

The question begged therefore is simple: wealth creation for who?

We live in a country where one quarter of adults have net savings of less than £100. Almost five million young people live with their parents because they can’t afford a home to call their own. Almost half of women (46%) have less than £10,000 in their pension pot. In a world where advancing technology is going to force us to re-skill constantly, a third of students will never afford to repay their student loan.

To fix this, we are going to need a bold strategy not merely of ‘levelling up’ places but ‘levelling up’ people’s wealth. That is why I argue in my book for a new architecture of universal basic capital (the subject of a second blogpost): a system that helps not just some but all build housing wealth, knowledge capital, short term savings and a decent pension for their golden years.

But none of this is free.

And given today’s fiscal black hole and our pledge not to touch income tax, national insurance or VAT, the time has come to restore fairness to tax and levy some taxes on the windfall gains in wealth of the very luckiest - so we can use the proceeds to help everyone, not merely some, build capital.

What would these taxes look like? We’re no longer short of options. In fact, a range of experts, like the Wealth Tax Commission, Demos, Patriotic Millionaires, the Tax Justice Network, have all tabled serious proposals. Tax expert Dan Neidle, who counsels against some of these ideas is in favour of reforming inheritance tax and capital gains tax, along with simplifying the current system and shutting down loop-holes.

Naturally, we will have to be careful about disincentiving investment, providing sensible carve-outs for entrepreneurs, protecting pension fund returns and minimising avoidance. But literally billions are available through measures like equalising the rate of capital gains tax with higher rate income tax, like the policy of that well-known socialist Nigel Lawson. It’s an idea that two Conservatives - David Willets and John Penrose advocate in a thoughtful piece for the Tory think-tank, Bright Blue.

Within limits, the impact of tax on growth owes far more to what you spend the money on - not how much you raise. But if we want a stable economy, we need stable politics and stable politics demands we fix wealth inequality. And we cannot fix wealth inequality without writing a tax code that reflects our moral code; a code that recognises it is time for those who’ve have done well these last few years to pay a little more. That shouldn’t be a tough choice.