Nearly, a decade on from the Brexit vote, trade will still be one the critical issues of 2025. Can we cosy closer to Europe and avoid Trump tariffs and somehow deepen trade in the world’s fastest growing new markets of China and the Asia-Pacific?

I think we can. In fact we have to. If we fail, the Government will not and cannot deliver its ambitions to become the fastest growing economy in the G7. So the grand challenge for Britain’s grand strategy is to reset relations with Europe, reassure America and de-risk trade with China.

That is certainly what the Prime Minister is aiming for. At the Liaison Committee yesterday, Keir Starmer told me that he thinks we can reset with Europe - and draw closer to the US. I asked the PM (see video) whether a EU SPS deal —a tighter veterinary deal—with the EU was compatible with a grand bargain free trade deal with the United States. The PM was fairly bullish.

“I think that we can pursue both” he said, “I do not accept the argument that you have to either be with the US or be with the EU. That is not how it works at the moment with our current trade. We do want a closer relationship with the EU on security, on defence, on energy and, yes, on trade, and I have set out how we want to reset on a number of occasions. At the same time, I want to improve our trading relationships with the US. Is that going to be easy? Of course it is not. Do I think we can make progress? Yes, I do.”

Personally, I think that is a tall order. But, let’s look closer at just what might be possible.

Step 1: Stop Tariffs

To put first things first, we have to forestall American tariffs. They would be a disaster. To achieve this, I think we have to couple trade diplomacy and security policy - as UK grand strategy at its best always has.

President Trump, rightly, wants Europe to spend more on defence. So we must point out to President Trump that bigger customs duties will mean smaller defence budgets. How much smaller?

Well, I asked the House of Commons Library to take a look.

Labour has made a 'cast iron commitment' to spend 2.5% of GDP on defence and the roadmap to 2.5% will come in the Strategic Defence Review. But if American tariffs shrink the size of our economy then that 2.5% will be worth less.

How much less?

For the sake of argument, let’s assume defence spending climbs from 2.33% of GDP to 2027-28 to 2.5% 2028-29 onwards. This is likely the earliest feasible roadmap for the increase to 2.5% and would imply defence spending £86.5 billion by 2030.

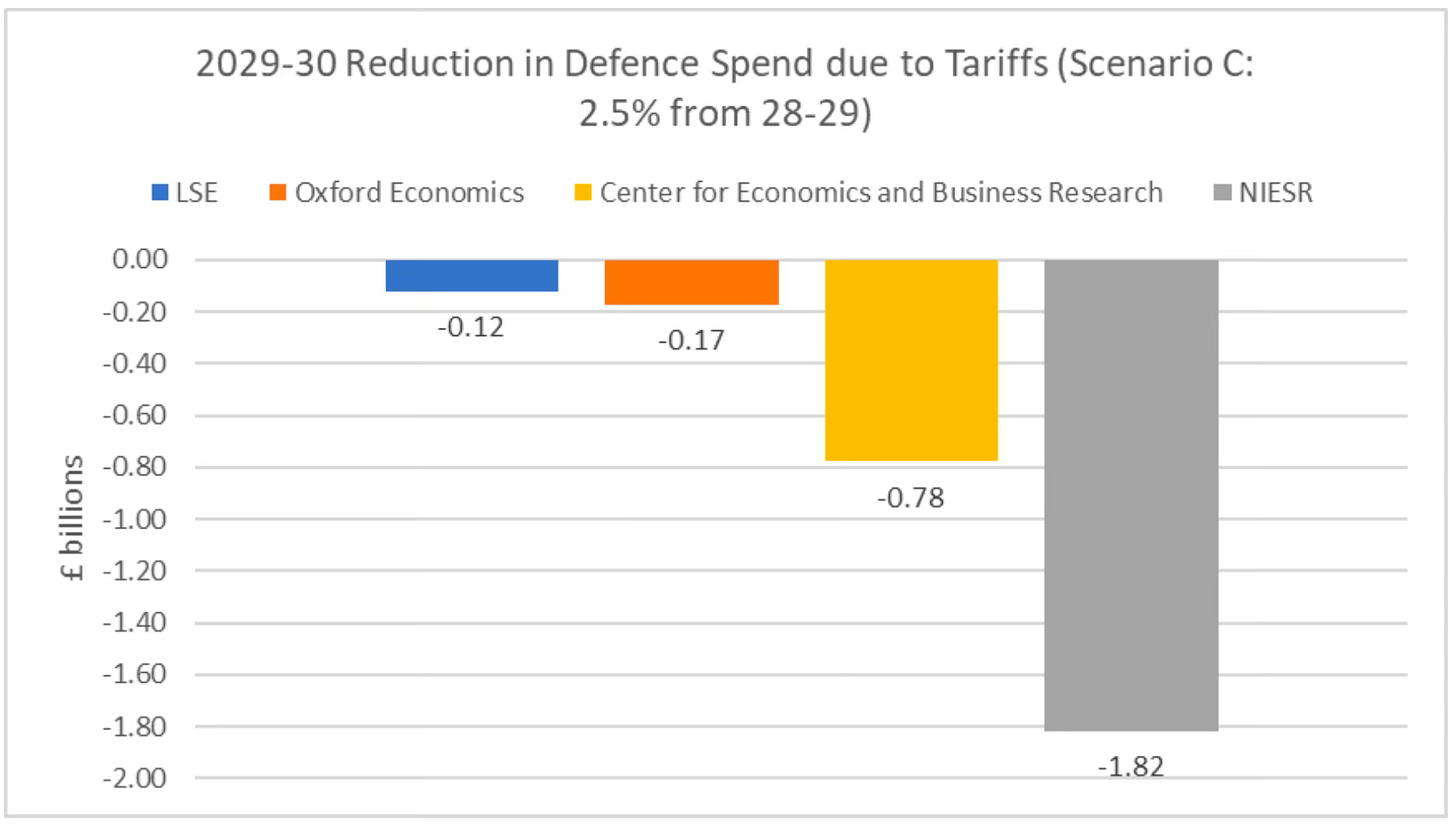

But if our economy is smaller because of tariffs, so defence spending will be less. Various think tanks and economists have modelled the likely impact on the UK economy of a 20% US tariff, including the London School of Economics, Oxford Economics, National Institute of Economic and Social Research, and the Centre for Economics and Business Research.

Using their numbers we can see that the tariff impact on our economy might entail a defence budget that shrinks by somewhere between £0.12 billion and (LSE) to £1.82 billion (NIESR).

That is one big way to explain to President Trump that tariffs are a bad idea. Especially if we couple it with a new set of guard rails to de-risk trade with China, which I explained here.

So, now it is time for step two: can we square deeper trade relations with the EU and the US? The answer is ‘probably’.

Step 2: Square Europe

An SPS agreement with Europe - which is Labour’s manifesto commitment - means reducing checks on agri-food products at the border. SPS agreements cut red tape like certifications, checks, and prohibitions, which are designed to ensure food safety for EU consumers and prevent the spread of pests or diseases by either harmonising rules or recognising them as equivalent.

An SPS deal is a big prize. In fact, Aston University think it is worth more than £3 billion worth of extra exports. But a deal will need detailed work from the Government to persuade the EU that the UK can implement a solution that protects UK and EU standards.

The trick, as the CBI has argued (in their short briefing), is to secure “an SPS agreement…[which] include[s] a regulatory mechanism that allows agri-food trade to be as smooth as possible without limiting the UK’s ability to make international FTAs.”

A couple of options are knocking around in recent blogs by Sam Lowe and UK in a Changing Europe:

Option 1: EU-Swiss Model: Full UK alignment with relevant EU rules, as applied to domestic production AND imports [to ensure non-compliant stuff doesn’t slip in by the back door] and probably some sort of role for the ECJ in determining whether the rules have been applied correctly. In practice this could probably be designed in a way, like the Withdrawal Agreement, where there is independent dispute settlement but on matters of interpretation of EU law the ECJ’s view has to be taken into account.

Option 2: EU New-Zealand Model (Mutual Recognition) Simplified declarations, and a reduced frequency of physical inspections at the border, but this model doesn’t remove the need for products to enter via a border control post and be subject to the associated document and identity checks.

These options are likely to be compatible to other FTAs that we have signed with, for example, Australia and CPTPP. Accession to these FTAs don’t automatically entail regulatory divergence with the EU, nor does it preclude us negotiating an SPS agreement with the EU. New Zealand (for example) has a veterinary agreement with the EU and is also a Party to CPTPP. The UKTPO has just published a blog on the question which concludes nothing in CPTPP precludes an UK- EU SPS agreement.

But, here’s the but.

The CPTPP SPS chapter does include things which depart from the EU’s ‘precautionary’ approach to food law. So if we start opting for ‘deep regulatory’ alignment with the EU then the probability goes up that we’ll start to have rows with with our new friends in the CPTPP.

Step 3: Realistic deepening with the US

So, what about the US? Here, I hear conflicting stories. When I listen to colleagues in Congress, they say there’s no interest in a sector by sector deal with the UK. They want a ‘grand bargain’ that includes agriculture, because in Congress the agriculture lobby is incredibly powerful.

But, given Trump’s dominance of the presidency, the House and the Senate, it may be likely that in the short-run at least, more narrow agreements - on economic security, critical minerals, and possibly digital or AI - might just be possible. But that means cracking on with the measures set out in the Atlantic Declaration, on which there has not been an awful lot of progress.

That falls short of a Free Trade Agreement with the United States, which I think would be a hell of an ask. And when I talk to the UK business community, they are not clamouring for it either. Trade with the US is already pretty friction-free, and lots of our advantages are in services which do not face many barriers.

In any full blown free-trade agreement, the US would be bound to push for Britain to bring its SPS regime into compliance with WTO rules. That would mean ‘risk-based’ reviews which are much lighter touch than the ‘hazard-based’ approach of the EU’s precautionary principle.

For example, the National Pork Producers Council and the U.S. Meat Export Federation (USMEF) might demand full equivalence of U.S. standards - which allow growth hormones or pathogen reduction treatments which are sold freely in the United States - but which are prohibited in the EU.

If we wanted to licence imports of this sort of stuff - produced to lower standards than sold in the EU - then the EU would insist on border controls to control re-exports of such things to the EU. The Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy has a good paper on the detail.

So: none of this is going to be easier. The devil will be in the detail. Progress will require cool heads but also a clear sense of the UK’s national interest and the extraordinary opportunity ahead: if we can find a way to become ‘the very point of junction’ between the great markets - a modern view of what Churchill would have called ‘the majestic circles’ - of the US, Europe and Asia Pacific, then great prizes might follow.

I’m grateful to the House of Commons Business & Trade Select Committee team for their work helping prepare the analysis set out here.

Share this post