Five ways to strengthen trade with Europe

If we want to fix Britain’s inequality problem we need an economy that grows faster. And that means stronger - not weaker - links to Europe.

Brexit has not been terrific for trade. It has proved hard to sign new trade deals around the world - not least because the world is fragmenting. And though our services exports to Europe have bounced back, goods exports, often sold by small business, have definitely suffered.

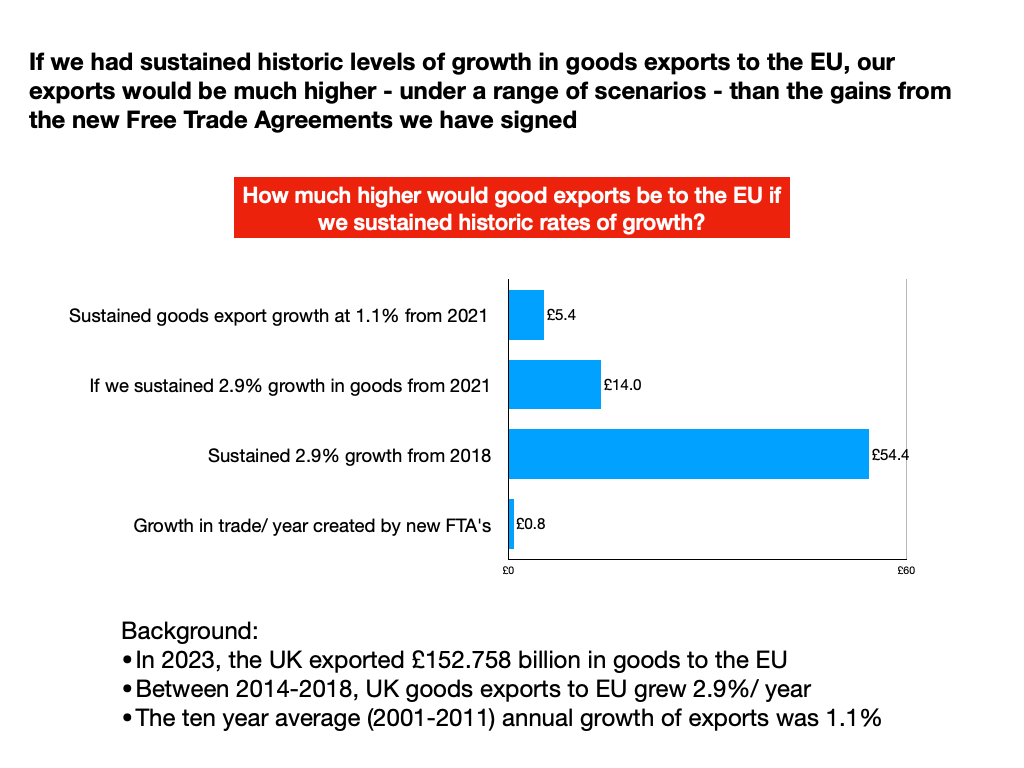

Brexiteers will disagree - as Lord Frost and others did when they came the Business & Trade Committee - and argue about quite what entrails we should inspect. But if goods exports to the EU had continued to grow at a range of historic rates, they would be higher today by somewhere between £5 billion and £50 billion a year. That dwarfs the gains from the new Free Trade Agreements we’ve signed which together add perhaps £800 million to trade a year.

Surprise, surprise, the Government is not so keen to lay this out. Instead, last week we were treated to an odd statement by the Secretary of State telling us how how well our trade was going.

The story didn’t take long to unravel.

The Resolution Foundation’s Emily Fry quickly posted figures showing we can’t disguise a poor story on European goods exports (though services were healthier).

Crucially, as Sky’s Ed Conway pointed out, Kemi’s figures weren’t adjusted for the massive amounts of inflation in recent years. In real terms, he wrote;

‘an ever-increasing volume of trade is actually a lot more flat. Goods exports…are still well below pre-Brexit.’

Nor did Kemi’s figures adjust for the vast amount of gold coming in and out of the country - about £28 billion of it. Subtract that from our exports and the UK is smaller exporter than France or the Netherlands.

As I gently pointed out in the Commons, we are still left, on the OBR’s figures, with the worst trade intensity in the G7, a point made by well by Ben Chu.

So: as we now stand back and survey five years work, we can see that we have just 60% of our trade now covered by the liberty of commerce enshrined in Free Trade Agreements. And it’s unlikely to much improve. When Greg Hands, the Trade Minister came before our select committee he admitted that he basically couldn’t promise any further deals would be done before the election.

What is more, these deals cover just a third of the global economy. And while a deal with India and the Gulf Cooperation Council might extend FTA coverage to just over half the global economy (52%), if a US and China deal remains off the table, the space to gain much from new trade deals is pretty limited, and indeed, the India and Gulf deals are forecast to add little to trade each year.

The case for Europe

So: having tried our hand at free trade agreements around the world - and largely failed - perhaps the logic now is to return to a tighter deal with Europe, not least because in this new world of geopolitical competition it makes sense to de-risk supply chains, critical minerals and investment security together with people who share our democratic values and a rule of law tradition.

Until the UK’s fabled ‘red lines’ change, the Trade and Cooperation Agreement remains about the limit of a deal that is possible with Europe - but trade diplomacy and dynamic alignment - or at least checks on ‘inadvertent dealignment’ - could actually make a big difference. The key to progress is understanding what Europe needs in the next five years, and where, therefore the win-wins might lie.

Atmospherics in Brussels have been transformed by the Windsor Framework, but for the years ahead, the challenge of Ukraine, China and the America’s huge investments in industrial policy will mean that there is new space for UK-EU cooperation in five areas:

economic security & defence, especially around support for Ukraine but more generally the shared objective of re-containing Russia;

maximising the potential of the Trade & Cooperation Agreement and rethinking dynamic alignment

building industries of the future and making the leap to net zero, especially transforming energy cooperation in the North Sea which could in effect become one of the world’s largest power stations helping both UK and EU hit challenging net zero targets.

maximising our shared economic security and coordinating our approach to China.

youth and service industry mobility.

Political uncertainty in Europe is high given elections everywhere. But the lead scenario in Brussels is seen as a second von der Leyen term, in which the President will draw heavily on the Draghi/ Letta reviews.

Given today’s global challenges, we will hear much more about ‘strategic autonomy’ for Europe, regardless of who wins the White House. Even if President Biden wins, there’s no expectation that the trade environment will improve; “it’ll be a truce but not peace” as one senior official in Brussels put it to me. Meanwhile, the Commission is now getting serious about tackling the un-level playing field with China: the Commission has launched its first investigations into EV cars, clean-tech, trains, medical devices and solar panels from China and more investigations are set to follow.

So, the challenge facing the EU is formidable: it has to simultaneously improve its competitiveness, de-risk supply chains and critical minerals, rearm, support Ukraine and keep accession moving forward and make the green transition - while having very little money to play with at Commission level. It needs friends to help it make progress and therein lies the opportunity for Britain.

The question therefore that the new Labour government must settle very quickly is, within a broader strategy for growth and security, how could closer ties with the EU help?

The loss of trade has hurt growth, and small business in particular may be losing competitiveness and productivity as the stimulus of exports is lost. But the basic logic of ‘securonomics’ is pretty straight-forward; in a world where we need to de-risk supply chains, it would make sense to secure better friction-free trade with our closest neighbour.

So how might this pan out?

While there are different views in Brussels about the virtue of more summitry, many do see a need for a re-set moment; a new PM-EU President Summit focused on ‘where we want to take the relationship’ - not ‘where do we want the TCA to go’.

That has to be backed up by a completely different tempo of ministers actually turning up in Brussels to put the kinetic energy into the day to day relationship building. Leo Doherty, the Minister for Europe, spent 29 days in Europe in 2023 - but zero days in Brussels. Indeed, throughout the year, FCDO ministers spent the grand total of nine days in the EU capital - about 2% of their travel time on the road in 2023. That. Is. Too. Little.

What might emerge from a new PM-EU President summit? I think there are probably five win-wins that would be good for both security and business.

Defence and security cooperation

This is stated Labour policy. The UK-EU political declaration included language about the virtues of defence and security collaboration - but this was never really followed up by Mr Sunak.

But tighter working together is absolutely vital as part of the joint effort to ensure Ukrainian victory and accession. If President Trump wins again there’s an expectation that defence spending will ramp up quickly and it would benefit us all if it was better coordinated.

This is not just about the principal battlefront in Ukraine but rather cooperation must stretch to a grander plan for the re-containment of Mr Putin; from better guarding of the submarine cables that land on the Irish continental shelf, to strengthening our presence in the Arctic, to building stronger relations - and supply chains for things like uranium - across Central Asia, where there is a keen appetitive to carefully diversify away from dependence on Russia.

The MultiDonor Platform for Ukraine and UK participation therein is seen as going well and there are now FCDO secondees into the EU-Ukraine team. Sanctions policy coordination is important and needs to deepen.

But beyond the conflict itself, there is then the business of Ukrainian accession to the EU, where again the UK can play an instrumental role in ensuring consistent messages - ‘rule of law, rule of law, rule of law’ - and supporting Ukraine in delivering on the accession process asks, especially anti corruption, media pluralism, protection of minorities, decentralisation, and rights of opposition parties. Progress towards accession is impossible without progress on these issues.

2. Maximising the opportunity of the TCA - and rethinking dynamic alignment

No-one I’ve met in Brussels think the TCA review is an opportunity for anything much. It’s a dry technical exercise and it’s some years away whereas new angles of cooperation need working straight-away.

EU officials underline that constraints of the TCA are dictated by the UK red-lines and not much is going to change if the red lines don’t change. As such, as one put it to me, ‘we’re at the limit of what can be done on trade without dynamic alignment.’

However, while TCA is a ceiling to cooperation there’s still lots to go at within it: connecting vehicle registration databases; intellectual property protection; health security; mutual recognition of qualifications; trusted trader schemes; digitalisation of veterinary certificates and lots more.

But the biggest opportunity is energy cooperation around North Sea wind interconnection and unlocking carbon storage capacity, of which we have around a quarter of Europe’s supply. Maximising this opportunity is vital for several member states hitting net zero targets.

The key fast approaching cliff-edge is Carbon Border Adjustment Mechansim (EU goes live 2026, UK 2027) where the large gap between UK and EU carbon prices creates a risk of what’s in effect a new tariff. Coordination and interconnection of Electricity Trading Systems is ‘absolutely essential’ by many in the Commission.

A far bigger opportunity emerges if the UK is prepared to accept dynamic alignment on goods regulations - or at least a deal on sanitary and phytosanitary measures that would help deal with the crazy new border checks. The Secretary of State seemed to think that this was necessary because of some sort of malicious intent of the EU. She told Iain Dale on LBC (16 April 2024)

“we didn’t originally raise [trade] barriers [with the EU]…the EU did. And that was one of the risks I think that we were aware of, that there might be some retaliation for us leaving […]

completely missing the point that trade friction arising from Brexit is an inevitable consequence of the UK becoming a “third country” outside the EU Single Market and Customs Union; it’s not “retaliation for us leaving”:

When we cross-examined the trade minister in this, it’s fair to say he was not a fan.

It’s a weary old argument. But let’s look at some new numbers. A new study from Aston Business School shows that a UK-EU SPS agreement could boost agri-food exports by an extraordinary 22%. This should persuade us to look at the whole question much more sympathetically.

3. Building industries of the future - and making the leap to zero carbon.

Like us, Europe faces huge challenges in mastering an industrial policy that will supply the good, well paid jobs of the future in a greener economy. The EU’s Net Zero Industry Act targets 40% of production in eight critical technologies to be domestically produced but the dilemma for Europe is that it cannot match the US-Inflation Reduction Act (which Breugel calculate at $3 million/job) and industrial policy subsidies are close to non-existent; after all the EU budget is but 1% of the EU’s GDP and 1/3 of that is spent on farmers.

Spending in those nations that can afford subsidies (Germany, France, and to an extent, Hungary) therefore risks disrupting the single market. Noone has solutions to this dilemma yet ands the risk is that without cash, the EU will regulate its way to net zero.

There are bold targets in Net Zero Industry Act though everyone expects political pressure to move the deadlines. Nevertheless, the challenge for the the UK business community is that it is clearly struggling to influence regulation and so many stress the critical need to get upstream of new regulation - of which there is an almost unprecedented amount - and for the UK to work harder to avoid ‘inadvertent divergence’. We will need to think about mechanisms to do this given how much new regulation is likely to flow from green transition laws.

But, given that ‘innovation is the power in super-power’ there surely must be scope for progress is in the field of research and development. For a place where scientists have been collaborating since the Scientific Revolution, we must find ways to build on the Horizon agreement to renew and deepen research and development ties.

4. Maximising economic security and coordinating the approach to China.

Given the perils of the new world we live in, if there is one obvious opportunity to build a realm of UK-EU cooperation beyond the TCA, it is to safeguard our mutual economic security. As one senior official in Brussels put it to me, ‘We face similar challenges now so there’s more space for cooperation’. But we need to be clear what we want out of it.

Collaboration on China policy could be a significant opportunity given our diplomatic and intelligence networks. But, we have to start getting serious about tackling the unfair playing field with China. There was amazement in Brussels that the UK did not join the EU in its anti-subsidy investigations - and this must be something we look at again. But, beyond this there are probably three key issues;

A/. Supply chains. EU officials argue it’s ‘absurd’ for us not to collaborate on understanding supply chain vulnerabilities and proactively safeguarding them together, including in those intermediate goods (eg permanent magnets) which are vulnerable to China throttling supply. New mechanisms might be needed here and it is worth noting the US IPEF framework, challenged as it is, nevertheless includes a supply chain chapter that basically creates early warning systems on risks.

B/. Critical minerals. Equally, on critical minerals, there may be scope to better coordinate development spending in global South, to help allies develop both green mining and processing, furthering the progress of a critical minerals ‘club’.

C/. Investment security. This is seen as poor in Europe and members states lack the company data to do it properly. This could be a field in which to expand cooperation on both inbound and outbound investment.

5/. Mobility.

Finally, there is the question of mobility. Labour has ruled out much progress here - to my surprise and frustration - but in Brussels this is seen as really important, not least to stop the ‘people to people bridge collapsing’ and a generation of children growing up in both Europe and Britain unable to participate in the sort of travel and exchange that so many of us enjoyed in our formative years. Personally, I’d go one step further and restore our membership of Erasmus; an enormously symbolic expression of a new will to rebuild a relationship that in time could become the foundation for better work visas which allow the UK services/ financial services/ creative economy the movement it desperately needs to thrive.

So. There is actually a huge amount that could be done together. Since the 1980’s, Britain has become a far more trade intensive economy - but the real shift was in the first decade of the 21st century, after which, frankly not much has changed:

So if we think trade is good for our economy - which I do - then in a more uncertain world, we need allies to draw closer not drift apart. New structures - like the European Political Community - will help a lot. But ultimately in the light of all we have learned since Brexit, closer ties needs both the will and the courage to lead the argument, and for us to escape the slavery to old arguments, so common in the last decade, that have turned out in the harsh light of reality, not to hold much truth.