Rage to riches (II)

How a new system of Universal Basic Capital can help us fix wealth inequality and defeat populism

The inequality of wealth is bad for our economy and worse for our politics. The general election results prove it. In regions and constituencies where the gains in wealth were lowest, the vote for Reform UK was highest. So, it is time for some bold new solutions.

Wealth inequality does not fix itself. Economists from James Meade to Thomas Piketty have shown time and again that left to its own dynamics, wealth inequality grows inexorably. Right now, we are a point of crisis. We need big new answers. And that is why at the core of my new book, the Inequality of Wealth, launched in paperback today I propose a big idea: Universal Basic Capital.

Why do we need such a thing? What does it look like? And how do we pay for it?

Let’s start with the ‘why’.

For most of my lifetime, wealth inequality was falling or flat. But in 2010 something changed. Over the last 14 years, the wealth of the top 1% has grown forty one times faster than the wealth of everyone else. The effect is an unheralded shift in our economy that shuts out millions from joining the wealth-owning democracy.

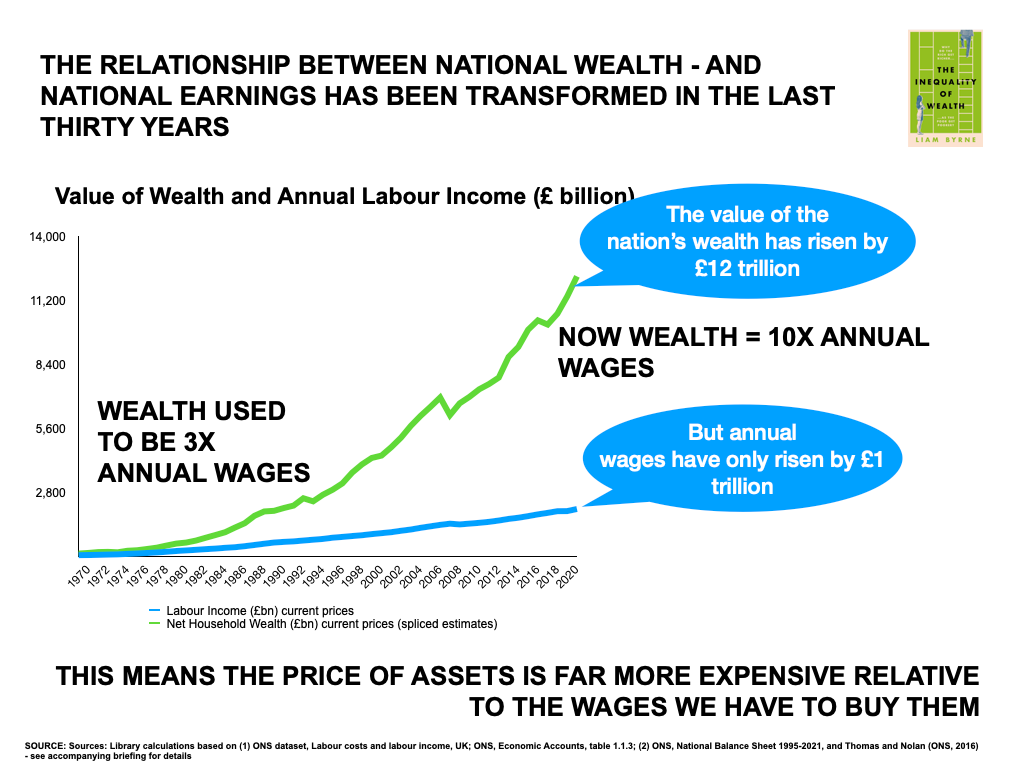

When I was born back in 1970, the wealth of the nation - which reflects asset prices - was around three times national wages. But that ‘wealth to wages’ ratio has now fundamentally changed. Today, the nation’s wealth is ten times the level of national wages. That means that assets - like homes - are far, far more expensive relative to what people earn.

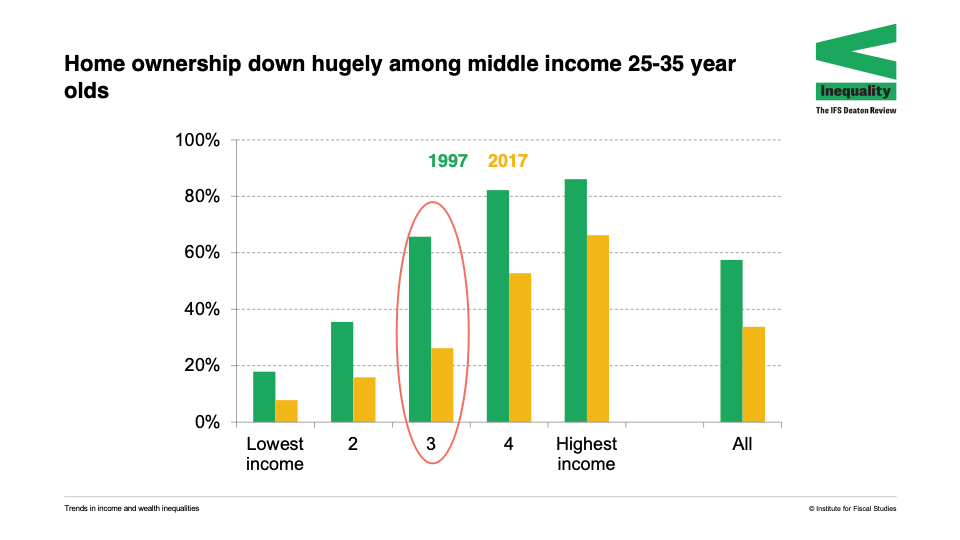

Young people are at the sharp end of this new reality. Millions are unable to afford a home to call their own or repay student debt or save for an adequate pension. The result? As the IFS shows, home ownership amongst middle income young people has collapsed over the last twenty years.

So how do we fix this and reinvent the ways we give people a stake in our economy? How do we rebuild the wealth-owning democracy?

Universal Basic Capital (UBC)

Many on the left have argued for the idea of universal basic income. Personally, I think the politics and the economics of this are insuperably difficult. But there is a better way: Universal Basic Capital (UBC), a new system that helps everyone build wealth - and share in the national wealth - over the course of their lives. Rooted in the ideas of the Nobel-prize winning economist, James Meade, UBC has three basic components:

A new Universal Savings Account, opened for all when they start work, and into which we pay…

A one-off Young Peoples’ Dividend worth upto £10,000, paid out of an enlarged National Wealth Fund which in turn is built bigger by using…

A handful of windfall taxes on the wealth of the luckiest in society who have seen their collective wealth surge by £1 trillion since 2010 thanks to £850 billion of quantitative easing (which we all happened to pay for).

How would this system work in practice?

Universal Savings Account

Universal Savings Accounts are an idea that, luckily enough, the nation has been road-testing for the last few years. It is based on one of the most successful innovations in public policy this century known as auto-enrollment pensions.

At work, you are now automatically enrolled in a pension scheme. Your contributions are automatically deducted from your pay-packet. Your employer adds to these as does the Government. You can opt out of the scheme but that is a bit of faff. This simple ‘nudge’ now means we have 21 million people now saving for a pension.

For a few years now, the National Endowment and Savings Trust, which is the default auto-enrolment pension provider, has experimented with auto-enrolling workers in both a pension savings account and a savings account known as ‘side-car accounts’ or Jars, now available to 80,000 workers. And guess what? It’s been a huge success. Indeed, NEST recently reported that after a year 97% of accounts were still open and that;

participating households had £384 median emergency savings balance at 12 months.

Given that a quarter of UK adults have savings of less than £100, this is a miracle. So, let’s build on this success and universalise the system for all young people when they start work. It would also provide a hugely important focus for financial literacy education at school.

But there is a problem. If young people have to rely on their own resources to build up their savings they will wait for an awful long time to amass enough to buy a home. And that is why we need to provide some help in the form of….

A one-off Young Peoples’ Dividend paid from a bigger National Wealth Fund

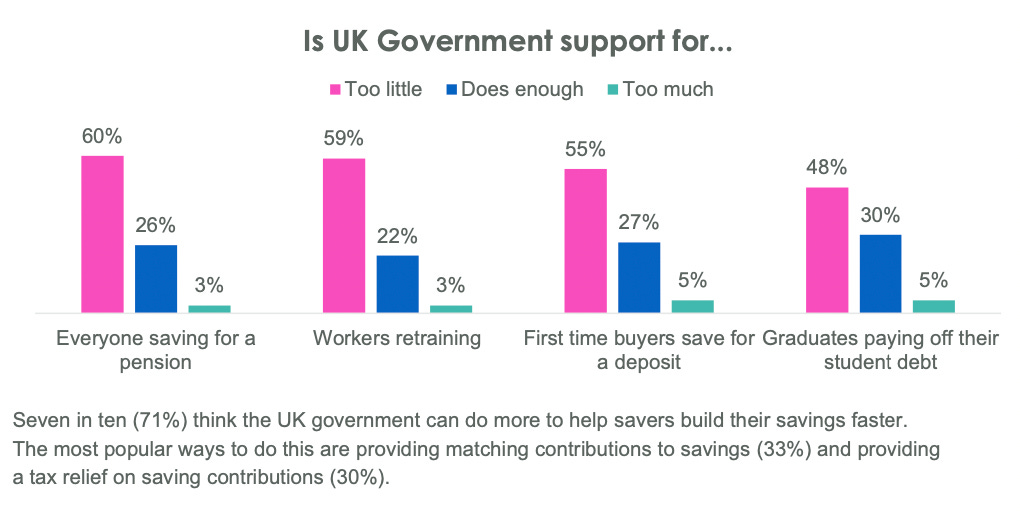

Today, people feel the government does too little to help people build long-term assets. In polling I undertook with Opinium, the Policy Institute at King’s College and the Fairness Foundation, we found that between 48-60% of the public say government does too little to help people save for pension, retrain, save for a deposit or pay off student debt.

It would help if there was a proper review of the labyrinth of government tax incentives for savings which currently route far bigger subsidies to the rich than the poor. But the key priority for me is helping young people save for a deposit on a home.

There is a slightly lazy view in Westminster that somehow we fix the home ownership problem by just building more homes - which we make easier by relaxing planning restrictions. This is part of the answer. But unless we transform housing finance we will not solve the problem, a point well made by Ian Mulherin, who notes,

even if planning reform did bring forward tens of thousands of extra homes each year, would that change the game on house prices? Not any time soon…Whatever way you look at it, a supply boom is not going to change the game for Millennials and the government shouldn’t pretend that it will.

The reality is that we will not drive up home ownership rates until we transform housing finance with (a) very long-term mortgage deals at fixed rates of interest (b) the return of 95% mortgages for first-time buyers (something proposed by the Tony Blair Institute) - and (c) crucially, a Young Peoples’ Dividend to help supply a deposit, because the lack of a deposit is the number one barrier to home ownership.

The Young Peoples’ Dividend is an evolution of a proposal from the Resolution Foundation’s Intergenerational Commission which proposed a one-off grant of £10,000 paid to every young person. Why £10,000? Well, that happens to be the average shortfall young people face when trying to put down a deposit for a home.

Our research shows there is a popular and an unpopular way to do this. My polling found that there is far more support for routing the money to young people not as a grant, but as as a savings match or tax break. Indeed, we found:

UK adults are divided on the idea of giving young people £10,000 at the age of 25. While 35% support the idea, 38% oppose the idea. This leaves a net support of -3%.

However, tax incentives that would see young people pay less income tax were much more popular even if it amounted to £10,000 and was paid for in the same manner. 41% support the idea, while 22% oppose. This leaves a net support of +19%, which is significantly higher than paying 25 year olds a lump sum.

So where do we get £10,000 for all 800,000 of the nation’s 25 year-olds? Roughly speaking that would cost the nation around £8 billion a year.

The answer is: a one-off dividend from an enlarged National Wealth Fund (more detail here).

Labour has already proposed such a fund but its principal purpose is to boost investment in stuff like infrastructure. No-one has really asked the question: what do we do with the fund’s returns?

So let’s learn a lesson from around the world. Globally, there are about 70 sovereign wealth funds as diverse – politically, geographically and culturally – as New Zealand, France, Ireland, most countries in the Arabian Gulf, and nine US states.

At least forty of these funds have been created since 2005. They are now amongst the most important investors on earth, delivering on average, something like an 8% annual return - and countries like Singapore use the funds to provide dividends for social investment like training and pensions.

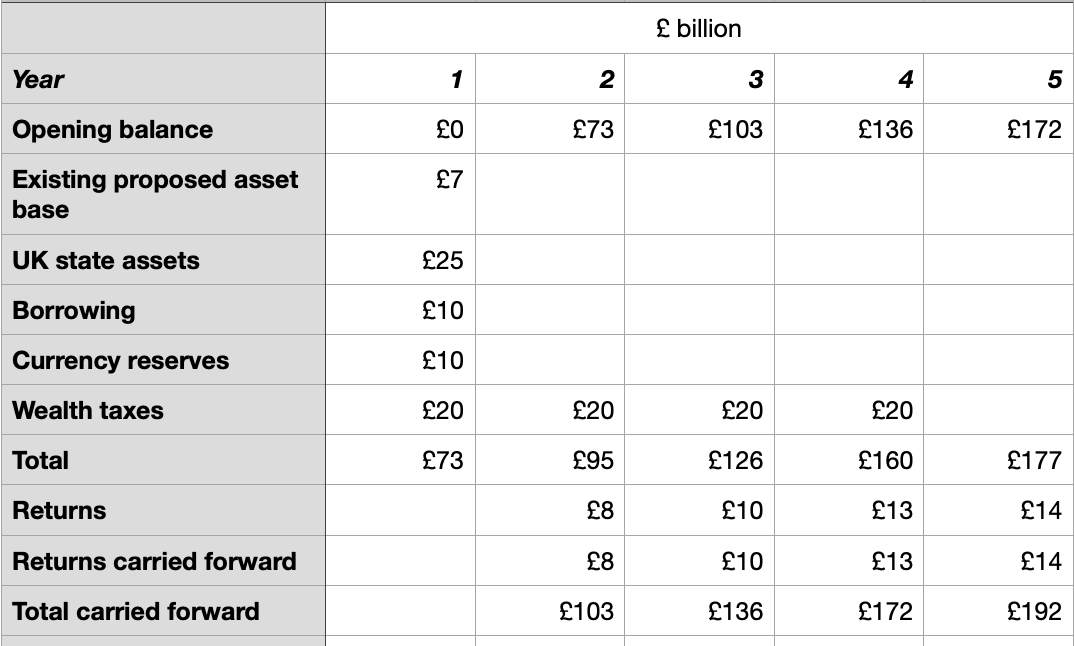

Assume we secured the same sort of returns. If we saved half the return (4%) to reinvest in the fund and paid out half (4%) as our Young Peoples’ Dividend, we see that to afford an annual dividend of £8 billion we need a National Wealth Fund of around £200 billion.

So, where do we get £200 billion? Well, we don’t enjoy huge natural resource windfalls (we gave away the proceeds of North Sea oil), so the reality is we would need to build a base of £50 billion from several core assets owned by the state. These might include:

Ring-fencing some state assets like shares in British banks (e.g. the government stake in Royal Bank of Scotland); the wind-down of UK Assets Resolution programme; the assets of the Crown Estate, and ‘dormant assets’ (the cash in UK bank and building society accounts that has lain untouched for fifteen years) plus future sales of the telecoms spectrum

A prudent degree of borrowing. This is do-able as the interest rates on 50 year gilts sits at about 4% - whereas returns to sovereign wealth funds average over 8%.

A prudent chunk - say 6-7% of the foreign exchange reserves (which total £149 billion), which is the approach taken by Singapore

If we then invested these assets and saved the returns for five years we would, at the end of year five, have amassed £192 billion. As long as we add in one thing more. An annual contribution of around £20 billion from some windfall taxes on wealth, for just four short years. So where do we get that from?

3. Windfall taxes on the nation’s luckiest

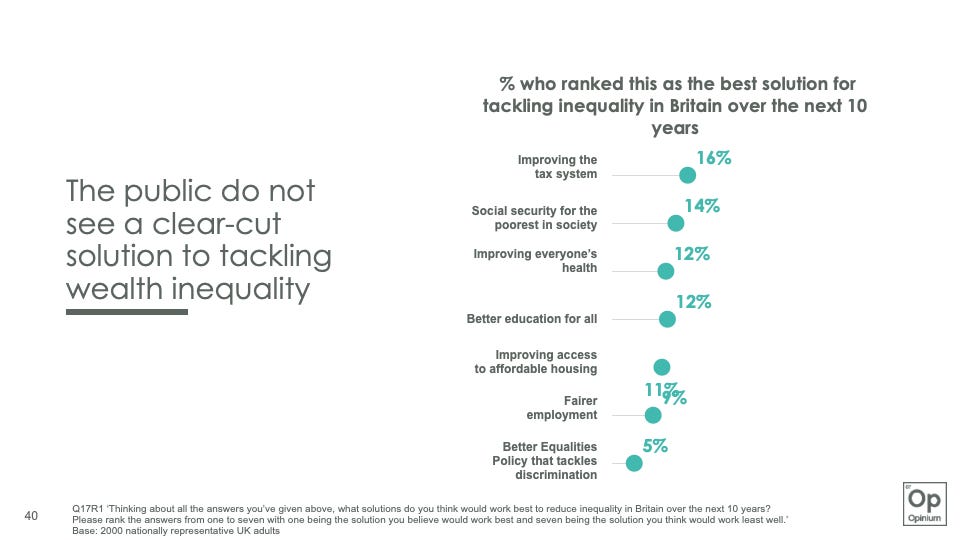

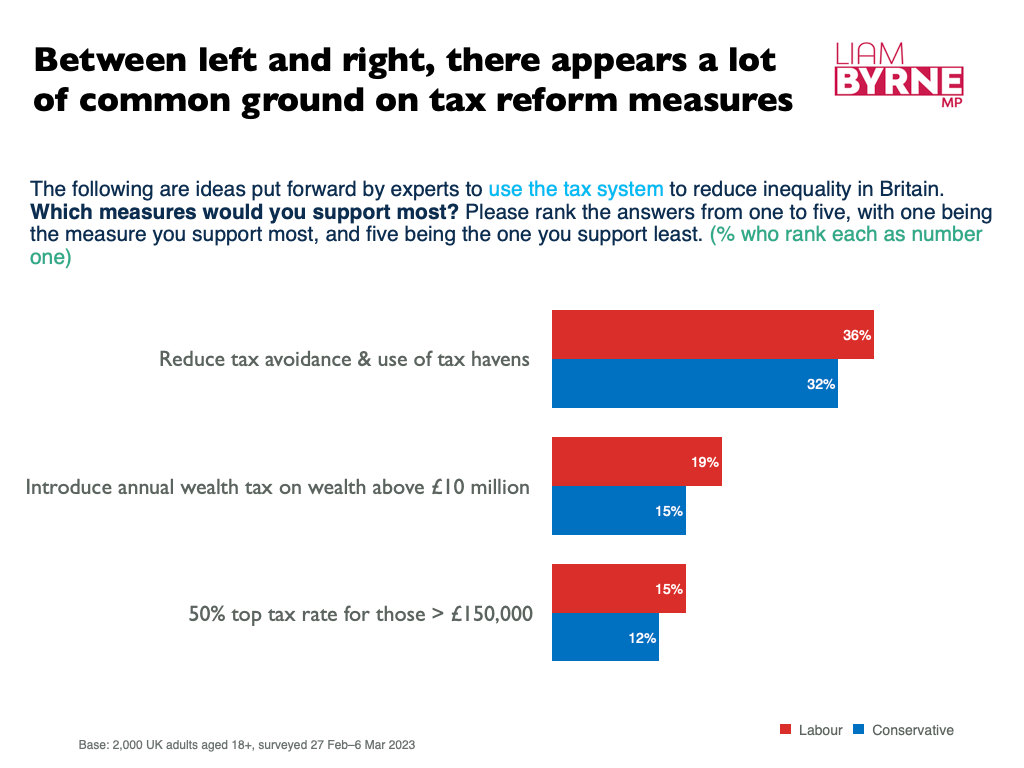

In our polling work, I’ve found that the public is worried about the size of the wealth gap between rich and poor. There is anxiety that it is getting worse and a clear majority want to see it reduced. When we tested a range of ideas for fixing the wealth gap, there was not one single stand-out type of measure the public priorities - but tax reform came top of the list.

Understandably, most people prioritise reducing tax avoidance as their preferred way to improve the tax system. But a remarkable number - on both left and right - cited a wealth tax on those with over £10 million in net assets as their second preferred options, ahead of higher income taxes on high earners.

In fact, there are now ten basic measures which are emerging in the debate on tax reform, worth up £60 billion a year, of which I list the top six in a rough order of political consensus (my judgement). Tax Watch UK also have an excellent summary.

Closing the loopholes enjoyed by Britain’s 37,000 ‘non-doms’. Currently hotly debated. There are two key loopholes: one allows non-doms to avoid UK inheritance tax on their worldwide estates if they are shielded in a trust (costing £430 million a year), while a second provides a 50% discount to tax paid on overseas income and capital gains in the first year, (costing £600 million). Estimates for the yield from reform range from around £1 billion to £3.2 billion.

Equalising, or near-equalising capital gains tax and income tax. 65% support equalising tax rates on income from wealth with income from work. Estimates of the proceeds range from around £8 billion to £15 billion to over £16.7 billion, depending on whether the rate is aligned with dividends tax rate or higher income tax rate.

Closing inheritance tax loopholes. Inheritance tax is very unpopular but is so riddled with loopholes (eighty-eight at the last count) that those estates worth over £10 million only pay a tax rate of 17% even though the headline rate is 40%. Reform could raise at least £1.4 billion a year by closing loopholes like business and agricultural property reliefs - and upto £6.5 billion if we embraced reform like the South Koreans.

Reform tax breaks enjoyed by the richest pension savers. Richer pension savers get a tax break on pension contribution at the higher tax rate. If they enjoyed just basic tax relief, we’d save £15 billion. But there would be unintended consequences to this. So the IFS proposes two alternatives; levying employer NICs (at 13.8%) on employer pension contributions (with an offset) which would raise £4½ billion, and subjecting pension pots to inheritance tax if and when they are passed on (potentially raising upto £2 billion a year).

Charging national insurance contributions on investment income. Under-discussed in the policy debate, but the idea is that we expand the tax base and charge NICs on income from investments like dividends from shares, rent from property, and interest on savings. Forecast to raise between £8.6 billion and £10.2 billion

Wealth tax of 1-2% on the 22,000 fortunes worth over £10 million. Polling shows strong political support for this (as long as it is a one off). A 2% wealth tax on assets over £10 million is forecast to raise up to £24 billion a year.

It does not look so hard to see one’s way to carving out £20 billion a year from this smorgasbord.

From experience I can tell you, it is very hard for those outside the Treasury to estimate accurately how much these taxes bring in. Indeed, it is pretty hard for the HMRC to get the estimates right. Lots of considerations come into play. How do we make sure the money comes in and the taxpayers do not simply leave the country? How do we avoid being a real outlier internationally? How do we preserve incentives for entrepreneurs to take risks and invest? How do avoid a hit to the returns to pension funds, and thus pensioners?

But if we take a step back, the big picture is simple: we can’t squeeze income tax, VAT and national insurance on working people any more. And given the spectacular windfall for asset owners of low interest rates, delivered by the quantitative easing we all paid for, there is a case for restoring fairness to the tax system and raising taxes on investment income which let us not forget goes overwhelmingly to the richest.

Taxes on capital income need to go up, and if we do it in the right way, we can use that money as a down payment to build a system of universal basic capital which begins to reverse the extraordinary growth of wealth inequality that now deeply divides our country.

Freedom in the 21st Century

For me, this is part of a big argument for how we renew and reinforce freedom and opportunity for new times. For centuries, philosophers and politicians have argued for the virtues of the property-owning democracy. It is an idea once celebrated by thinkers on the both the right and left. Today, that big goal of renewing what we might today call the wealth-owning democracy should unite us because there is no freedom worth its name without security. And there is no security without wealth.