Britain may be mired in a cost of living crisis, but make no mistake, these are good times for some.

If the nation’s richest fancy a bite to eat they can pop into Aragawa where a prime slice of cow costs over £760. Or an evening on the tiles? Perhaps a stay at the new Raffles hotel on Whitehall, where a room might set you back up to £25,000? A night. Or perhaps you’d like a home to call your own? On Britain’s most expensive street, Phillimore Gardens, a humble abode now averages £23.8 million. You could buy a whole street in my constituency for that.

These extraordinary prices are the hallmarks of a new inequality of wealth, driving demand for the most luxurious things imaginable. In 2021, the order books for super-yachts made by yards like Pendennis in Falmouth (where I visited last year) were packed with a thousand super-craft under construction or on order. Every year, another 230 boats join the global fleet, worth perhaps £9 billion. Demand for private jets – which cost up to £36 million each – is forecast this year to reach its highest level ever. Sales of Rolls Royce’s luxury cars, which roll off its production line (which looks more like a medical clinic) in the Sussex Downs, are at the highest level in history.

And of course, if you’ve really made it, you don’t want a mere Roller. You need a rocket.

Who can forget Amazon’s founder, Jeff Bezos, blasting off into the azure American sky to become the first man to pay his way into outer space? Over eleven glorious minutes, his oddly phallic-looking 18-metre-high spaceship crossed the Kármán Line, which notionally divides our atmosphere from space, ascending 66.5 miles above the earth before falling back, with a sonic boom, to a dusty landing in the West Texas scrublands.

‘Best day ever!’ he declared. ‘My expectations were high and they were dramatically exceeded.’ Dressed in a blue jumpsuit and a cowboy hat, he then proceeded to lay credit where credit was due: ‘I… want to thank every Amazon employee and every Amazon customer. Cause you guys paid for all this.’

But Bezos was not alone. Ten days before his space adventure, the 70-year-old British billionaire Richard Branson flew a 90-minute trip on his SpaceShipTwo to just below the Kármán Line, while in September 2021, Elon Musk watched his SpaceX firm launch four people into earth’s orbit for a three-day journey.

The trophies of the super-rich – the exquisite toys, the gilded, gated palaces, the tiny rockets, the small jets, the giant yachts – are now the stuff of modern myth and legend. But at a time when food banks in my constituency are running out of food, is it not, as Bernie Sanders put it to me, ‘the absurdity of affluence’?

The rise of the super-rich is a global phenomenon, and in the United States, Bernie Sanders, is the American politician who has probably had the most to say about it. We recently found ourselves together at a British American Parliamentary Group conference. White-haired and intense, Bernie has an electric smile that comes alive whenever someone asks for a selfie – which is all the time.

I put it to him that the conspicuous consumption of the American super-rich was surely now more extreme than the days of the Great Gatsby.

‘Absolutely, said Bernie,

‘it is probably worse than it was in what we call the Gilded Age. You have people who are competing with each other as those yachts are getting bigger. You’re seeing all of these people on their own jets.

‘They live in mansions all over the world. Some of them own their own islands. I mean, the absurdity of this affluence is so great that you’re seeing people like Bezos or Musk literally going off into outer space on their little spaceships.’

‘So yes,’ he concluded, ‘you are seeing an extraordinary level of greed, of opulence, of contempt for ordinary people.’

The story of wealth inequality in Britain is different to America, or Russia, or China or India. In the work of writers like Catherine Belton, or James Crabtree, or Desmond Shum, we can study the dynamics of the billionaire boom around the world.

But what about Britain?

Since I was born in the holy town of Warrington back in 1970, Britain’s wealth has multiplied 100-fold to just shy of £13 trillion. That’s enough to pave a path of gold, six bullion bars wide, from Land’s End to John O’Groats.

For much of my life, wealth inequality was falling. But that trend stopped in the 1980s, and since 2010 the growth in wealth inequality has been truly extraordinary.

In fact, all told, since 2010, the top 1% have multiplied their wealth by an incredible thirty-one times more than everyone else.

It turns out that if you…

run an economy in the way we do

bail out the banks (financial services make up nearly a quarter of all profits in Britain)

throw in nearly a trillion of pounds worth of quantitative easing to keep interest rates low and inflate the value of assets

pump in almost half a trillion pounds worth of business support during Covid

and then charge half the rate of tax on investment income paid by top rate income tax payers

…then the richest are bound to get, well richer. Not least, because so much of their income is now drawn from investments – which are taxed far more lightly than wages.

As the nation’s net wealth has tripled this century, to almost £13 trillion, so investment income has risen. In fact, House of Commons library calculations which I’ve commissioned show the nation’s investment income has approximately doubled to around £80 billion a year.

This investment income flows, overwhelmingly, to the better off in society. The data is very hard to assemble because of under-reporting, but based on DWP data, the House of Commons library reckons around 60% of all investment income flows to just the top 10% of households.

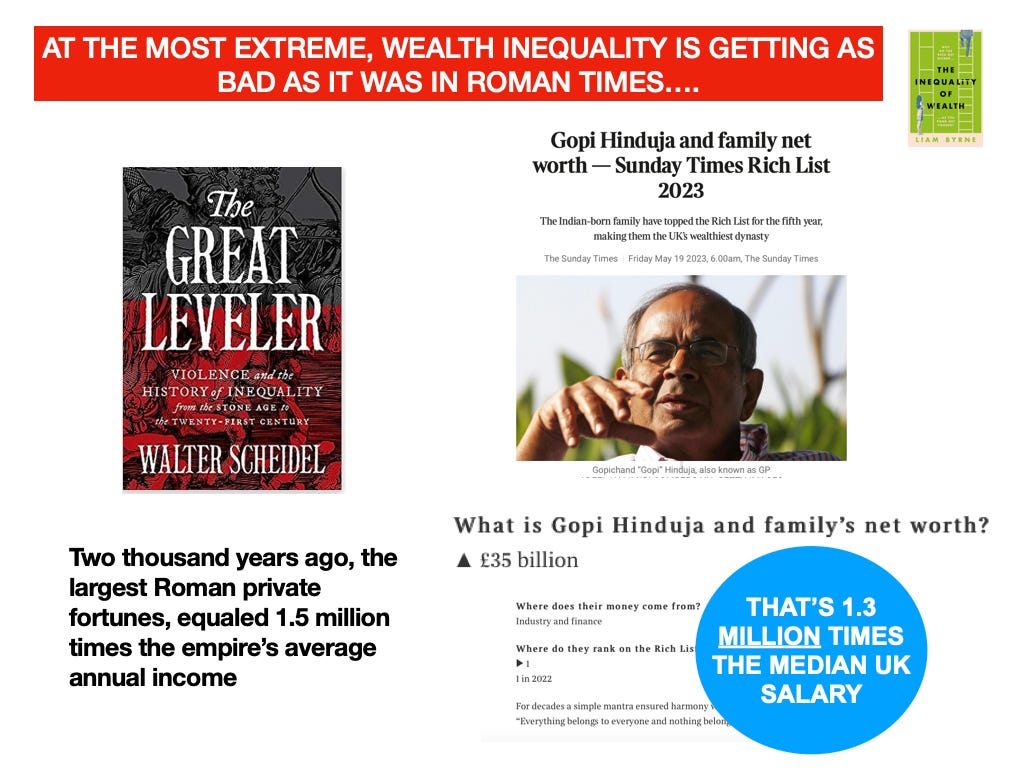

The cumulative effects of these changes are now extraordinary. At its most extreme, the UK’s level of wealth inequality is almost Roman. Walter Scheidel, in his brilliant history of inequality, reckons that in Roman times the largest fortunes were around 1.5 million times the average income of a Roman citizen. Well, guess what? According to the Sunday Times Rich List, the wealth of Gopi Hinduja and his family – at £35 billion – would be 1.3 million times the median UK salary.

Yet, unchecked, these trends will all get worse. Much worse. And that will be bad for both our economy, our society – and crucially, our politics.

We have to change course. But how? In my new book, The Inequality of Wealth. Why it matters and how to fix it, I try to unpack just how we’ve ended up where we are, and crucially, where we go from here.

Ultimately this is going to require us figuring out solutions which people will not merely like on social media, but vote for in an election. And so, next week I’ll share our research on just what the British public thinks!

If you’d like to pre-order the book, it is right here. Thanks for reading!

Dear Liam,

I've just read your articles and find myself in full agreement. For the last 20 years in my business, we've been working to address inequalities in many of the UK's highly deprived communities through enabling people to 'give themselves a job' (and social and financial and economic inclusion, a better future for themselves and their children, and a break in the cycle of deprivation and generational unemployment) through enterprise education and support. Many of these have little or no skills, and multiple disadvantages - and yet our 3 year survival rates beat the national average.

Whilst Chair of the IED until the end of last year, I led a piece of research into Social Value in Construction, "From the Ground Up", revealing much of it to be highly tokenistic, when, if done with meaning and purpose it could be a force for good to help level up. I often give talks about our rising, structural and deepening inequalities, and how this is going to take more than a generation and a short term policy to fix, though there are of course some immediate levers that can be applied. It is a moral imperative that we as a nation, and as a government, fix this sickening wealth disparity, especially given the rise in food banks and child poverty.

You have my support!

Bev Hurley CBE