The Populist Trap: What Labour Must Learn from the Local Elections

Five charts that show chasing Reform voters to the right risks unraveling the progressive coalition Labour needs to win the next general election

As Parliament returns next week, there’ll be plenty of political pathologists conducting their post-mortems on both the council results and the extremely narrow defeat in Runcorn.

I’ll be publishing much more on the rise of populism in the months to come as part of a collective effort on Decoding Populism, kicking off with a fascinating study of populist rhetoric across the West which underlines the absolute imperative for Labour of developing a simple, compelling, emotionally resonant story about how we will restore the nation’s fortunes, and harness the extraordinary changes in the world to enlarge people’s security, freedom, opportunity, and agency to live the lives they want.

But in the meantime, here are five charts as a reminder against any knee-jerk response to ‘shift right’ in response to last week’s results. It isn’t who we are and nor does it make any electoral sense for Labour.

Here’s five charts to light up the argument.

First, it is obvious that Labour needs a clear strategy to deal with Reform. There are, I think, now 89 seats where Reform is in second place to Labour—largely because the Tory vote collapsed. Labour’s majorities over Reform in these constituencies vary widely—from a 4% majority in Llanelli to a whopping 56% majority in Bootle.

This simple fact alone means we have to ensure we have a clear plan to combat Reform. Seventy five of these seats had a lower margin of victory over Reform than Labour used to enjoy in Runcorn; in 2024, Labour’s margin over Reform UK was 34.8%. Only twelve Labour-held seats where Reform is second to Labour, enjoy a bigger margin than that. And as last week illustrates the importance of this task may grow in the years ahead for if the Tories fail to recover, the threat from Reform will grow even greater.

Kemi Badenoch has proven to be a disastrous leader. It’s hard to find a single Tory MP in Westminster with an ounce of confidence in the so-called renewal process now underway. I suspect the ritual self-purification of the party—a rite all losing parties tend to undergo—has barely begun.

In the absence of a more powerful Conservative Party, there is a risk that, as in Runcorn, Reform not only takes votes from Labour but also consolidates the anti-Labour vote on the right. That’s a much bigger threat to Labour. A rough look shows there are 144 seats where the combined Tory and Reform vote exceeds the current Labour majority.

But a generalised ‘shift to the right’ is unlikely to be Labour’s best defence.

I was keen to get back to Runcorn. It’s where I spent the first five years of my childhood. And every Labour canvasser I spoke to in Runcorn said the same thing: like me, they met many people who weren’t thrilled with Labour, were disappointed by some of the tough decisions we’ve made—but were absolutely determined to stop Reform. So they were going to hold their noses and vote Labour. As it turned out, there weren’t quite enough of them in the Runcorn by-election to hold the seat for Labour, as turnout compared to the general election fell by 14%.

But in a general election, Labour must absolutely seek to mobilise an anti-Reform progressive coalition at scale—and we can do that so long as we don’t undermine our progressive credentials between now and polling day.

Take another look at those 144 seats where a Tory-Reform combination could defeat Labour. It turns out that in 101 of them - i.e. 70% - the combined Labour, Lib Dem, Green, and ‘other candidates’ (generally Independents) vote is larger than the combined Tory-Reform vote. The progressive coalition, if we can hold it together, is bigger than the combined forces of the Right in more than a hundred seats.

Now, things are never as simple as this. Many Lib Dems for instance are more right wing than you might think. But at the last election, Labour was absolutely testing to near destruction how far it could go without alienating progressive voters. We should avoid this. But the basic logic was neatly set out by Ben Ansell this morning:

…if Reform really are able to continue polling at thirty percent, it’s going to be a very tough ride for Britain’s two traditional major parties. Labour could continue in power but it will need them either to push their own vote share up or to ally effectively with both the Lib Dems and the Greens.

Jane Green and Marta Miori underline the point:

Go after Reform voters by moving to the right on key issues like immigration and the liberal-left voters, as well as those who are currently undecided and stayed at home, may not coalesce behind Labour to the degree that they did in 2024.

Two final charts.

Even if Labour shifted radically to the Right, it could never consolidate the entirety of the Reform base. Remember, 70% of Reform’s 2024 general election vote came from the Conservatives. According to Prof Jane Green and Marta Miori today;

“At the 2024 election, according to our analysis of BES data, only 5% of 2024 Labour voters saw Reform as their preferred (more ‘liked’) party among those they didn’t vote for.’

As such, there are limits to the share of the Reform vote that Labour can realistically attract. Well over half of Reform voters identify as being on the right. There is a group who identify as left-leaning on economics - but look at this chart from the Financial Times. The average Reform voters clusters slightly to the Right.

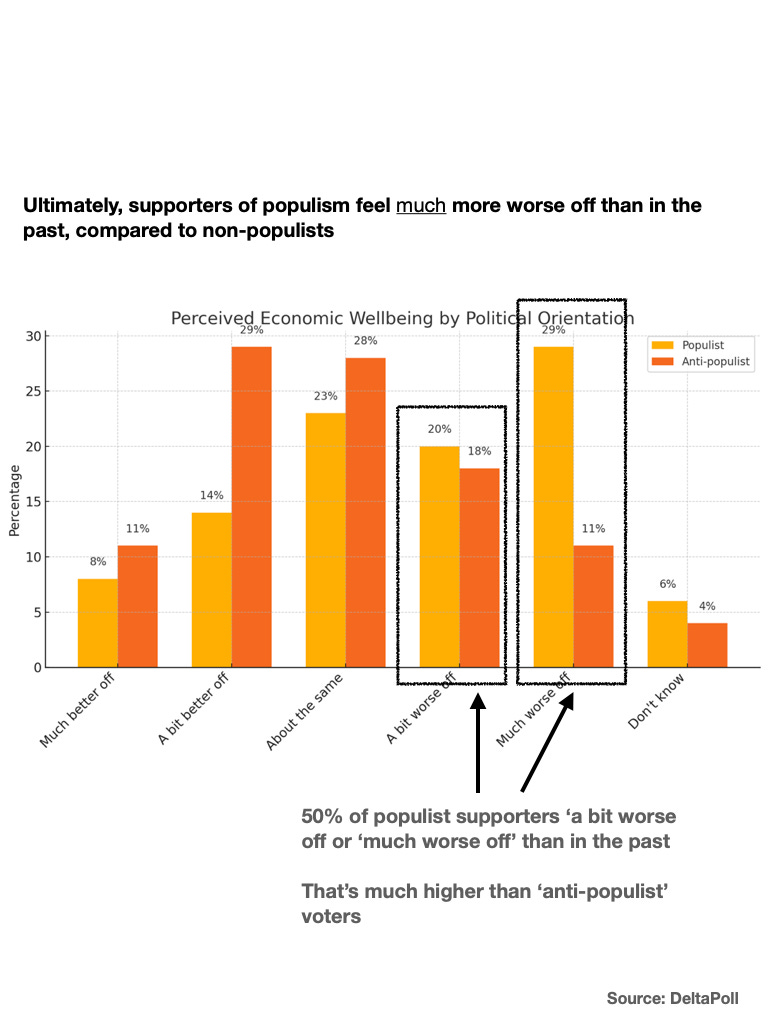

Now, we might realistically seek to win that cluster of Reform voters who while culturally might live on the right, are, economically are on the left. They may well be part of the very large group of populist voters who told DeltaPoll they are worse off, or much worse off, than in the past. And as I wrote after the General Election, there is obviously a relationship between a relationship between the new inequality of wealth that divides our country, and electoral support for Reform.

Typically, populist supporters are workers or retired people who may have left school earlier than others. Even if they are now retired and on a pension, my experience is that they’re angry that their fixed incomes are being eroded by bills that never seem to stop rising. For understandable reasons, they are exhausted by austerity and pessimistic about the future. They see the world in zero-sum terms.

So when governments - who they deeply distrust and overwhelmingly blame for their economic prospects - are seen to be giving to some, they assume this must mean less for them; less in disability benefits (even though they’ve paid in), less for adaptations like a downstairs wet-room or walk-in shower for their disabled partner, less investment in their area to fix the pavements, the potholes, or to spruce up the local shops or the park, less for policing to tackle the insane epidemic of speeding, or the chaotic parking outside schools at drop-off and pick-up.

These are the basic challenges Labour has to fix. But in the next few weeks it is going to be vitally important that Labour gets two reforms right: immigration reform and social secuirty reform. Both are needed.

There is plenty still to do fix our immigration system. I feel this deeply because I spent two years as Minister for Borders and Immigration, creating the £2 billion UK Border Agency, introducing the points system and biometric visas and putting in place plans for ID cards. Crucially, I hope Yvette Cooper gets to finish the reforms I started but could not finish to create ‘earned citizenship’ and introduce (at least digital) ID cards. This is about showing the state can work and delivering on procedural justice. What we cannot and must not do is jeopardise our duties under the ECHR, which in a world falling apart, is one of the legal frameworks that holds together what I’ve called the ‘rights-based order’ of nations.

We need to be far, far more cautious about social security reform and any sense that we are slicing back disability benefits in an unthinking way or ditching our net zero ambitions is an error.

Social security in particular has high potential to go wrong - and remember as LSE noted back in 2021 “poor health and disability are connected to lower levels of trust ..and that this disengagement may even lead…to increased support for right-wing populist parties.” The same year, American Political Science Review analyzed data from the European Social Survey (2002–2020) and found that “voters with worse self-reported health were significantly more likely to vote for right-wing populist parties.” Get social security wrong, and populist support will go up.

Labour was founded on the idea, enshrined in Clause 4, that through the strength of our common endeavour we achieve more than we achieve alone. So Keir is right to say we need to go further, faster. But in doing so, we ought to be clear that we are determined to let Labour be Labour - and that we plan to avoid doing the things that progressive, compassionate parties try to avoid, like increasing inequality, poverty, and vulnerability.

Denmark’s Social Democrats have found success by combining progressive economic policies with a firm stance on immigration. There’s a decent article in the New York Times that explores this in detail. While we’re unlikely to go far enough for some Reform voters, we can demonstrate credibility by delivering real progress on immigration reform - ending Channel crossings, reducing reliance on hotels, and acknowledging legitimate concerns about social cohesion. This could help us win over some One Nation Conservatives, particularly as their new party veers further to the right.

What’s preventing us from adopting this approach while also advocating for a wealth tax and supporting people properly?

Has it been you or Torsten who wants to go on Gary Stevenson’s channel? I’ve pointed our MP in your direction, as there’s unanimous support within our CLP for establishing a new government-backed Wealth Tax Commission, building on the independent LSE commission.

Morgan McSweeney needs to be let go.